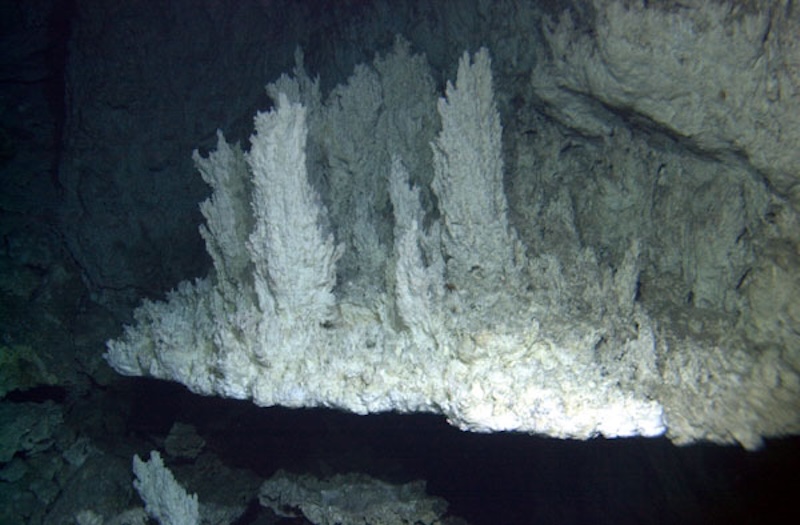

Photo: National Science Foundation (University of Washington/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

via Wikimedia Commons (Public domain)

Deep in the ocean, near an underwater mountain in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, lie a series of carbonate “towers” that rise from the inky depths to create a jagged landscape. With only the light of remote-operated vehicles sent to examine the site, these structures appear eerie and ghostly. The various towers clustered together give them an urban feel, leading scientists to call this natural wonder the Lost City.

The Lost City Hydrothermal Field was first discovered in 2000, over 2,300 feet below the surface. It is the longest-living vented environment in the ocean, and nothing like it has been found in the years since its discovery. Scientists estimate this unique underwater vent field has been in existence for at least 120,000 years, maybe longer.

Despite this structure’s desolate ocean surroundings, its designation as a “Lost City” isn't quite apt. The upthrusting mantle reacts with seawater to disperse methane, hydrogen, and other gases out into the ocean. As a result, novel microbial communities survive in the nooks and crannies of the vent system, managing to live even without oxygen thanks to the presence of hydrocarbons produced by the towers’ chemical reactions. Some of the calcite towers also double as chimneys; they spew gases at temperatures as high as 104 degrees Fahrenheit and house a variety of crustaceans and snails. Larger species, such as shrimp, sea urchins, crabs, and eels, have also been found near the site, but with significantly less frequency.

Aside from being a natural wonder, understanding Lost City is key to understanding ourselves. The hydrocarbons produced in these mineral vents occur as a result of chemical reactions on the deep seafloor, not due to carbon dioxide or sunlight. Because hydrocarbons are also known as the building blocks of life, the chemical processes that take place in the Lost City could be the very same ones that began life on Earth, and potentially on other planets.

In 2018, William Brazelton, a microbiologist, told Anna Kusmer at The Smithsonian that, “this is an example of a type of ecosystem that could be active on Enceladus or Europa right this second.” The idea that the moons of Saturn and Jupiter could have similar conditions for life is an exciting one. And, there's more to be discovered about Lost City. Researchers announced in 2024 that they were able to successfully recover a core sample of mantle rock from the site.

Lost City is the only thermal field of its kind, making it valuable for the knowledge we can, and are, gleaning from it. But developments in mining rights to the surrounding deep sea may have negative impacts on the impressive mineral vent system. Amid calls to designate the natural wonder as a World Heritage site, we must act swiftly to protect the Lost City, not just for its impressive look, but also for its potential to unlock the secrets of life itself.

An underwater “Lost City” located in the deep-sea Mid-Atlantic Ridge may hold the key to understanding how life on Earth began.

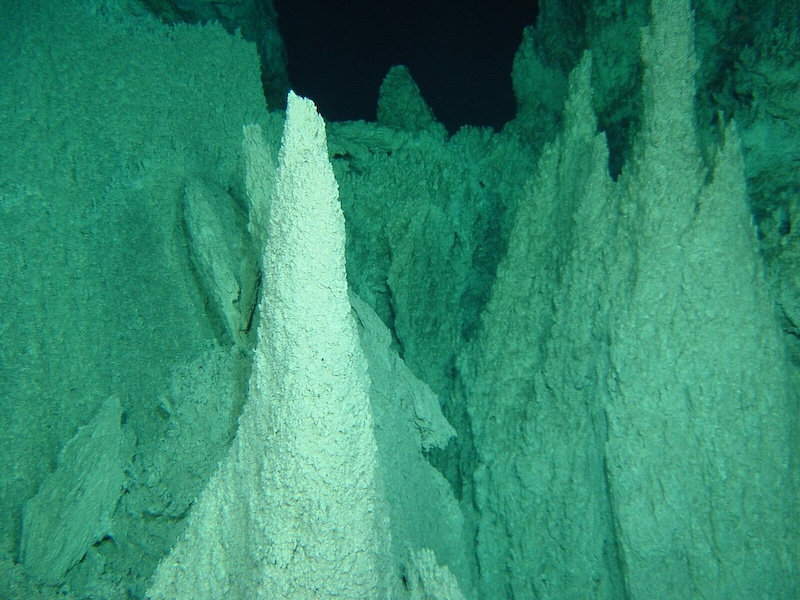

Photo: OptimusPrimeBot via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The hydrothermal field contains a series of jagged “towers,” which are made of mineral carbonate.

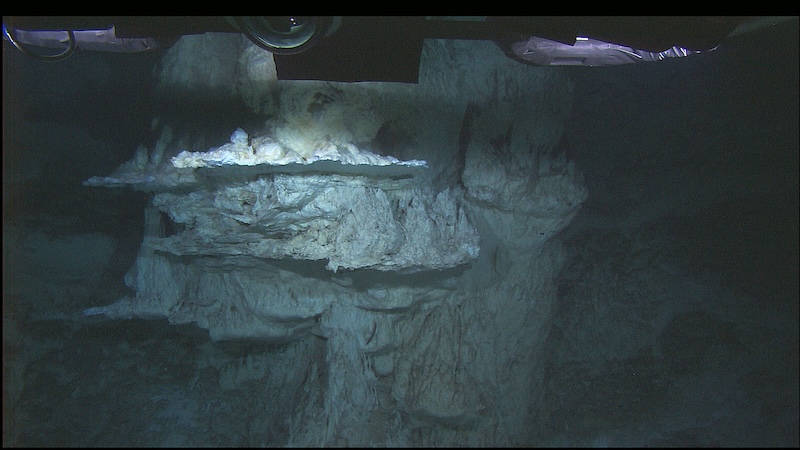

Photo: Susan Lang, U. of SC. / NSF / ROV Jason / 2018 © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Despite its extreme environment, the Lost City is home to a few critters due to its production of hydrocarbons, as a result of deep-sea chemical reactions.

Photo: Susan Lang, U. of SC. / NSF / ROV Jason / 2018 © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Scientists believe that examining the Lost City's mineral conditions may offer more clues into how life came to be, on this planet and beyond.

Photo: NOAA via Wikimedia Commons (Public domain)

Sources: Diving Deep to Reveal the Microbial Mysteries of Lost City

Related Articles:

Mysterious Ancestor Connecting All Life on Earth Is 200 Million Years Older Than We Thought

Researchers Discover 7,000-Year-Old Underwater Road

Researchers Discover World’s Oldest Water in a Mine Nearly 2 Miles Underground

Explorers Have Discovered the World’s Deepest Shipwreck 22,621 Feet Under the Sea